And the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics goes to… October 8, 2013

Posted by apetrov in Particle Physics, Physics, Science, Uncategorized.trackback

Today the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to François Englert (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium) and Peter W. Higgs (University of Edinburgh, UK). The official citation is “for the theoretical discovery of a mechanism that contributes to our understanding of the origin of mass of subatomic particles, and which recently was confirmed through the discovery of the predicted fundamental particle, by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.” What did they do almost 50 years ago that warranted their Nobel Prize today? Let’s see (for the simple analogy see my previous post from yesterday).

The overriding principle of building a theory of elementary particle interactions is symmetry. A theory must be invariant under a set of space-time symmetries (such as rotations, boosts), as well as under a set of “internal” symmetries, the ones that are specified by the model builder. This set of symmetries restrict how particles interact and also puts constraints on the properties of those particles. In particular, the symmetries of the Standard Model of particle physics require that W and Z bosons (particles that mediate weak interactions) must be massless. Since we know they must be massive, a new mechanism that generates those masses (i.e. breaks the symmetry) must be put in place. Note that a theory with massive W’s and Z that are “put in theory by hand” is not consistent (renormalizable).

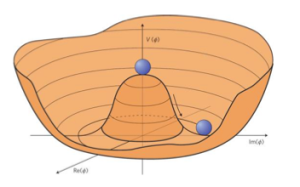

The appropriate mechanism was known in the beginning of the 1960’s. It goes under the name of spontaneous symmetry breaking. In one variant it involves a spin-zero field whose self-interactions are governed by a “Mexican hat”-shaped potential

It is postulated that the theory ends up in vacuum state that “breaks” the original symmetries of the model (like the valley in the picture above). One problem with this idea was that a theorem by G. Goldstone required a presence of a massless spin-zero particle, which was not experimentally observed. It was Robert Brout, François Englert, Peter Higgs, and somewhat later (but independently), by Gerry Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, Tom Kibble who showed a loophole in a version of Goldstone theorem when it is applied to relativistic gauge theories. In the proposed mechanism massless spin-zero particle does not show up, but gets “eaten” by the massless vector bosons giving them a mass. Precisely as needed for the electroweak bosons W and Z to get their masses! A massive particle, the Higgs boson, is a consequence of this (BEH or Englert-Brout-Higgs-Guralnik-Hagen-Kibble) mechanism and represents excitation of the Higgs field about its new vacuum state.

It is postulated that the theory ends up in vacuum state that “breaks” the original symmetries of the model (like the valley in the picture above). One problem with this idea was that a theorem by G. Goldstone required a presence of a massless spin-zero particle, which was not experimentally observed. It was Robert Brout, François Englert, Peter Higgs, and somewhat later (but independently), by Gerry Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, Tom Kibble who showed a loophole in a version of Goldstone theorem when it is applied to relativistic gauge theories. In the proposed mechanism massless spin-zero particle does not show up, but gets “eaten” by the massless vector bosons giving them a mass. Precisely as needed for the electroweak bosons W and Z to get their masses! A massive particle, the Higgs boson, is a consequence of this (BEH or Englert-Brout-Higgs-Guralnik-Hagen-Kibble) mechanism and represents excitation of the Higgs field about its new vacuum state.

It took about 50 years to experimentally confirm the idea by finding the Higgs boson! Tracking the historic timeline, the first paper by Englert and Brout, was sent to Physical Review Letter on 26 June 1964 and published in the issue dated 31 August 1964. Higgs’ paper, received by Physical Review Letters on 31 August 1964 (on the same day Englert and Brout’s paper was published) and published in the issue dated 19 October 1964. What is interesting is that the original version of the paper by Higgs, submitted to the journal Physics Letters, was rejected (on the grounds that it did not warrant rapid publication). Higgs revised the paper and resubmitted it to Physical Review Letters, where it was published after another revision in which he actually pointed out the possibility of the spin-zero particle — the one that now carries his name. CERN’s announcement of Higgs boson discovery came 4 July 2012.

Is this the last Nobel Prize for particle physics? I think not. There are still many unanswered questions — and the answers would warrant Nobel Prizes. Theory of strong interactions (which ARE responsible for masses of all luminous matter in the Universe) is not yet solved analytically, the nature of dark matter is not known, the picture of how the Universe came to have baryon asymmetry is not cleared. Is there new physics beyond what we already know? And if yes, what is it? These are very interesting questions that need answers.

Very interesting. I think there will be Is more last Nobel Prize for particle physics.